Friday, March 02, 2007

With the spectre of a national election haunting the collective Australian psyche it was interesting to read Judith Wheeldon's article in the WEEKEND AUSTRALIAN 3-4 th of March, 2007. The title of the article sums up our collective dilemma: Labor the lesser evil. Are we only offered to choose or make the best of a bad situation? Wheeldons assertions regarding the inherent dangers of a National Curriculum (especially one based on narrow short term thinking) is at best divisive, costly and erosive of intellectual diversity on a national level.

Whilst I feel that standardization of marks whether it be on a personal level or a national level has merit these indicators are just that and nothing more . They are a general guide of a direction tendency or outcome and they are only accurate as these if the sum of the wisdom of the parts of the intent, scope, outcomes and diversity of the tests for the marks that are being standardized.

Friday, February 09, 2007

First principles of instruction

This article or section is incomplete and its contents need further attention.

Some sections may be missing, some information may be wrong, spelling and grammar may have to be improved etc. Use your judgement !

Contents

[hide]

1 Definition

2 The five principles of instruction

3 Implications for educational technology

4 Links

5 References

[edit]

Definition

First principles of instruction is a attempt by M. David Merrill to identify fundamental invariant principles of good instructional design, regardless pedagogic strategy. It can be used both as an instructional design model and as evaluation grid to judge the quality of a pedagogical design

First principles of instruction is the title of a frequently cited on-line paper in several versions, e.g.

Merrill, M. D. (2002). First principles of instructions, Educational Technology Research and Development, 50(3), 43-59.

Merrill, M. D. (in press). First Principles of instruction, in C. M. Reigeluth and A. Carr (Eds.). Instructional Design Theories and Models III. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

[edit]

The five principles of instruction

Merrill's first and central principle of instruction is task-centered learning. Task centered learning is not problem-based learning, although it shares some features.

The task / problem

A task is a problem that represents a problem that may be encountered in a real-world situation. Learning objectives or samples of the types of problems learners will be able to solve at the end of the learning sequence may also substitute for a problem. A progression through problems of increasing difficulty are used to scaffold the learning process into manageable tiers of difficulty.

Does the courseware relate to real world problems?

... show learners the task or the problem they will be able to do/solve ?

are students engaged at problem or task level not just operation or action levels?

... involve a progression of problems rather than a single problem?

This progressive teaching approach is also related to Merriënboer's 4C/ID model.

The five principles of instruction (Merrill, 2006)

The demonstration principle: Learning is promoted when learners observe a demonstration

The application principle: Learning is promoted when learners apply the new knowledge

The activation principle: Learning is promoted when learners activate prior knowledge or experience

The integration principle: Learning is promoted when learners integrate their new knowledge into their everyday world

The task-centered principle: Learning is promoted when learners engage in a task-centered instructional strategy

Phases / Components of Merrill's First Principles of Instruction

The task (or problem) is center stage. Here is a summary of the four remaining components

Activation of relevant previous experience promotes learning by allowing them to build upon what they already know and giving the instructor information on how to best direct learners. Providing an experience when learners previous experience is inadequate or lacking to create mental models upon which the new learning can build. Activities that stimulate useful mental models that are analoguous in structure to the content being taught can also help learners build appropriate schemas to incorporate the new content.

Does the courseware activate prior knowledge or experience?

do learners have to recall, relate, describe, or apply knowledge from past experience (as a foundation for new knowledge) ?

does the same apply to the present courseware ?

is there an opportunity to demonstrate previously acquired knowledge or skill ?

Demonstration through simulations, visualizations, modelling, etc. that exemplify what is being taught are favoured. Demonstration includes guiding learners through different representations of the same phenomena through extensive use of a media, pointing out variations and providing key information.

Does the courseware demonstrate what is to be learned ?

Are examples consistent with the content being taught? E.g. examples and non-examples for concepts, demonstrations for procedures, visualizations for processes, modeling for behavior?

Are learner guidance techniques employed? (1) Learners are directed to relevant information?, (2) Multiple representations are used for the demonstrations?, (3) Multiple demonstrations are explicitly compared?

Is media relevant to the content and used to enhance learning?

Application requires that learners use their knew knowledge in a problem-solving task, using multiple yet distinctive types of practice Merrill categorizes as information-about, parts-of, kinds-of, and how-to practice that should be used depending upon the kind of skill and knowledge identified. The application phase should be accompanied by feedback and guidance that is gradually withdrawn as the learners' capacities increase and performance improves.

Can learners practice and apply acquired knowledge or skill?

Are the application (practice) and the post test consistent with the stated or implied objectives? (1) Information-about practice requires learners to recall or recognize information. (2) Parts-of practice requires the learners to locate, name, and/or describe each part. (3) Kinds-of practice requires learners to identify new examples of each kind. (4) How-to practice requires learners to do the procedure. (5) What-happens practice requires learners to predict a consequence of a process given conditions, or to find faulted conditions given an unexpected consequence.

Does the courseware require learners to use new knowledge or skill to solve a varied sequence of problems and do learners receive corrective feedback on their performance?

In most application or practice activities, are learners able to access context sensitive help or guidance when having difficulty with the instructional materials? Is this coaching gradually diminished as the instruction progresses?

Integration in effective instruction occurs when learners are given the opportunity to demostrate, adapt, modify and transform new knowledge to suit the needs of new contexts and situations. Reflection through discussion and sharing is important to making new knowledge part of a learner's personal store and giving the learner a sense of progress. Collaborative work and a community of learners can provide a context for this stage.

Are learners encouraged to integrate (transfer) the new knowledge or skill into their everyday life?

Is there an opportunity to publicly demonstrate their new knowledge or skill?

Is there an opportunity to reflect-on, discuss, and defend new knowledge or skill?

Is there an opportunity to create, invent, or explore new and personal ways to use new knowledge or skill?

[edit]

Implications for educational technology

The task-centered principle

This section needs to be completed a lot, see [http://cito.byuh.edu/merrill/text/papers/Reiser%20First%20Principles%20Synthesis%201st%20Revision.pdf First principles of instruction: a synthesis, p 7ff.

Learning is promoted when learners engage in a task-centered instructional strategy 'and' when a progression through problems of increasing difficulty is used to scaffold the learning process into manageable tiers of difficulty and whole-tasks are broken down to part-tasks (components)

The Instructional Sequence in Merrill's First Principles of Instruction

To design the first four phases (activation - demonstration - application - integration), whole tasks have to be broken down into components and the components have to be analyzed. Then one has to decide what should be taught in what way.

Merrill suggests to teach individual components with a direct instruction approach (which is more efficient and often also more effective). Most tasks or problems include five different instructional compontents. Firstly. initial "telling" should always activate prior knowledge. Demonstration (phase 2) should focus on adequate portayals of components (but linked to the whole), before the application phase is entered. Here are few hints on how to tell/demonstrate different sorts of components:

Information-about

Tell facts or associations and link them to previous knowledge

Parts-of

Tell names and descriptions

Portrayal: Show location

kinds-of

Tell definition

Portrayal: Show examples and counter-examples

how-to

Tell about steps and sequence

Portrayal: Illustrate steps for specific cases (work-through examples)

what-happens

Tell about the process as a whole, conditions, consequences

Portrayal: Illustrate specific conditions and consequences for specific cases

In the third (application) phase students have to work on skills related to portayals and then put "things together" in the forth (integration) phase.

Each increasingly difficult whole task (problem) requires going back and forth from (1) demonstration of the whole task (2) to component "teaching" and (2) back to integration. Once the whole task is mastered, this procedure is repeated which the next whole task until the "real world" problem is mastered without much "direct component teaching".

A few principles for teaching materials and learning activities

Components of Merrill's First Principles of Instruction

Navigation

Learners should see how contents are organized

They should be able go forth and back, correct themselves

Motivation

Learning environments should be interesting, relevant and achievable

Real tasks are more motivating than formal objectives, glitz and novelty

Known content is not motivating, students should be able to skip over

Performing whole tasks is more motivating then decontextualized actions and operations

Immediate feed feedback decreases motivation - delayed judgement increases (interesting, this is not like direct instruction)

Collaboration

Favor small groups (2-3) to optimize interactions

Group assigments should be structured around problems (whole tasks), i.e. "real" products or processes

Interaction

Navigation is not interaction (i.e. it is not cognitive interactivity)

Interaction means solving real-world problems or tasks

Key elements are: a context, a challenge, a learner activity and feedback.

See also the pebble in the pond model that outlines a simple instructional design method that can be used to design a learning environment according to Merrill's principles of instruction. Additionnally there is also the issue of levels of instructional strategies , i.e. what we get when we do less ...

[edit]

Links

M. David Merrill's home page (more articles)

A New Framework for Teaching in the Cognitive Domain by Molenda, Michael, ERIC Digest.

[edit]

References

Merrill, M. D. (2002). First principles of instruction. Educational Technology Research and Development, 50(3), 43-59. PDF Preprint, retrieved, 17:17, 15 September 2006 (MEST)

Merrill, M. D. (in press). First Principles of instruction, in C. M. Reigeluth and A. Carr (Eds.). Instructional Design Theories and Models III. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. PDF Preprint, retrieved, 17:17, 15 September 2006 (MEST)

Merrill, M. D. (In Press). First principles of instruction: a synthesis. In R. A. Reiser and J. V. Dempsey (Eds.) Trends and Issues in Instructional Design and Technology. Columbus: Ohio, Merrill Prentice Hall. PDF Preprint, retrieved, 17:17, 15 September 2006 (MEST)

Categories: Incomplete | Instructional design models | Evaluation methods and grids

Article

Discussion

Edit

History

Log in / create account

Navigation

Main Page

Random page

Help

Editing rules

big_brother

New Pages

Recent changes

Popular Pages

User List

All Pages

TECFA_links

TECFA

TECFA Portal

Search

Google search

(better, but behind)

Toolbox

What links here

Related changes

Upload file

Special pages

Printable version

Permanent link

Cite this article

Visualize this article

Gagne's Nine Events of Instruction: An Introduction

by Kevin Kruse

Just as Malcolm Knowles is widely regarded as the father of adult learning theory, Robert Gagne is considered to be the foremost researcher and contributor to the systematic approach to instructional design and training. Gagne and his followers are known as behaviorists, and their focus is on the outcomes - or behaviors - that result from training.

Gagne's Nine Events of Instruction

Gagne's book, The Conditions of Learning, first published in 1965, identified the mental conditions for learning. These were based on the information processing model of the mental events that occur when adults are presented with various stimuli. Gagne created a nine-step process called the events of instruction, which correlate to and address the conditions of learning. The figure below shows these instructional events in the left column and the associated mental processes in the right column.

Instructional Event

Internal Mental Process

1. Gain attention

Stimuli activates receptors

2. Inform learners of objectives

Creates level of expectation for learning

3. Stimulate recall of prior learning

Retrieval and activation of short-term memory

4. Present the content

Selective perception of content

5. Provide "learning guidance"

Semantic encoding for storage long-term memory

6. Elicit performance (practice)

Responds to questions to enhance encoding and verification

7. Provide feedback

Reinforcement and assessment of correct performance

8. Assess performance

Retrieval and reinforcement of content as final evaluation

9. Enhance retention and transfer to the job

Retrieval and generalization of learned skill to new situation

Gain attention

In order for any learning to take place, you must first capture the attention of the student. A multimedia program that begins with an animated title screen sequence accompanied by sound effects or music startles the senses with auditory or visual stimuli. An even better way to capture students' attention is to start each lesson with a thought-provoking question or interesting fact. Curiosity motivates students to learn.

Inform learners of objectives

Early in each lesson students should encounter a list of learning objectives. This initiates the internal process of expectancy and helps motivate the learner to complete the lesson. These objectives should form the basis for assessment and possible certification as well. Typically, learning objectives are presented in the form of "Upon completing this lesson you will be able to. . . ." The phrasing of the objectives themselves will be covered under Robert Mager's contributions later in this chapter.

Stimulate recall of prior learning

Associating new information with prior knowledge can facilitate the learning process. It is easier for learners to encode and store information in long-term memory when there are links to personal experience and knowledge. A simple way to stimulate recall is to ask questions about previous experiences, an understanding of previous concepts, or a body of content.

Present the content

This event of instruction is where the new content is actually presented to the learner. Content should be chunked and organized meaningfully, and typically is explained and then demonstrated. To appeal to different learning modalities, a variety of media should be used if possible, including text, graphics, audio narration, and video.

Provide "learning guidance"

To help learners encode information for long-term storage, additional guidance should be provided along with the presentation of new content. Guidance strategies include the use of examples, non-examples, case studies, graphical representations, mnemonics, and analogies.

Elicit performance (practice)

In this event of instruction, the learner is required to practice the new skill or behavior. Eliciting performance provides an opportunity for learners to confirm their correct understanding, and the repetition further increases the likelihood of retention.

Provide feedback

As learners practice new behavior it is important to provide specific and immediate feedback of their performance. Unlike questions in a post-test, exercises within tutorials should be used for comprehension and encoding purposes, not for formal scoring. Additional guidance and answers provided at this stage are called formative feedback.

Assess performance

Upon completing instructional modules, students should be given the opportunity to take (or be required to take) a post-test or final assessment. This assessment should be completed without the ability to receive additional coaching, feedback, or hints. Mastery of material, or certification, is typically granted after achieving a certain score or percent correct. A commonly accepted level of mastery is 80% to 90% correct.

Enhance retention and transfer to the job

Determining whether or not the skills learned from a training program are ever applied back on the job often remains a mystery to training managers - and a source of consternation for senior executives. Effective training programs have a "performance" focus, incorporating design and media that facilitate retention and transfer to the job. The repetition of learned concepts is a tried and true means of aiding retention, although often disliked by students. (There was a reason for writing spelling words ten times as grade school student.) Creating electronic or online job-aids, references, templates, and wizards are other ways of aiding performance.

Applying Gagne's nine-step model to any training program is the single best way to ensure an effective learning program. A multimedia program that is filled with glitz or that provides unlimited access to Web-based documents is no substitute for sound instructional design. While those types of programs might entertain or be valuable as references, they will not maximize the effectiveness of information processing - and learning will not occur.

How to Apply Gagne's Events of Instruction in e-Learning

As an example of how to apply Gagne's events of instruction to an actual training program, let's look at a high-level treatment for a fictitious software training program. We'll assume that we need to develop a CD-ROM tutorial to teach sales representatives how to use a new lead-tracking system called STAR, which runs on their laptop computers.

1. Gain attention

The program starts with an engaging opening sequence. A space theme is used to play off the new software product's name, STAR. Inspirational music accompanies the opening sequence, which might consist of a shooting star or animated logo. When students access the first lesson, the vice president of sales appears on the screen in a video clip and introduces the course. She explains how important it is to stay on the cutting edge of technology and how the training program will teach them to use the new STAR system. She also emphasizes the benefits of the STAR system, which include reducing the amount of time representatives need to spend on paperwork.

2. Inform learners of objectives

The VP of sales presents students with the following learning objectives immediately after the introduction.

Upon completing this lesson you will be able to:

List the benefits of the new STAR system.

Start and exit the program.

Generate lead-tracking reports by date, geography, and source.

Print paper copies of all reports.

3. Stimulate recall of prior learning

Students are called upon to use their prior knowledge of other software applications to understand the basic functionality of the STAR system. They are asked to think about how they start, close, and print from other programs such as their word processor, and it is explained that the STAR system works similarly. Representatives are asked to reflect on the process of the old lead-tracking system and compare it to the process of the new electronic one.

4. Present the content

Using screen images captured from the live application software and audio narration, the training program describes the basic features of the STAR system. After the description, a simple demonstration is performed.

5. Provide "learning guidance"

With each STAR feature, students are shown a variety of ways to access it - using short-cut keys on the keyboard, drop-down menus, and button bars. Complex sequences are chunked into short, step-by-step lists for easier storage in long-term memory.

6. Elicit performance (practice)

After each function is demonstrated, students are asked to practice with realistic, controlled simulations. For example, students might be asked to "Generate a report that shows all active leads in the state of New Jersey." Students are required to use the mouse to click on the correct on-screen buttons and options to generate the report.

7. Provide feedback

During the simulations, students are given guidance as needed. If they are performing operations correctly, the simulated STAR system behaves just as the live application would. If the student makes a mistake, the tutorial immediately responds with an audible cue, and a pop-up window explains and reinforces the correct operation.

8. Assess performance

After all lessons are completed, students are required to take a post-test. Mastery is achieved with an 80% or better score, and once obtained, the training program displays a completion certificate, which can be printed. The assessment questions are directly tied to the learning objectives displayed in the lessons.

9. Enhance retention and transfer to the job

While the STAR system is relatively easy to use, additional steps are taken to ensure successful implementation and widespread use among the sales force. These features include online help and "wizards", which are step-by-step instructions on completing complex tasks. Additionally, the training program is equipped with a content map, an index of topics, and a search function. These enable students to use the training as a just-in-time support tool in the future. Finally, a one-page, laminated quick reference card is packaged with the training CD-ROM for further reinforcement of the learning session.

JIGSAW GROUPS FOSTER UNDERSTANDING among students from a variety of racial, ethnic, and educational backgrounds. This learning method enables teachers to effectively respond to a diverse student population by promoting academic achievement and cross-cultural understanding. Jigsaw groups facilitate learning because each student is responsible for a particular piece of a task and then is responsible to contribute his/her portion of the task to bring about mutual interdependence.

The Set Up

To create five groups of four students, have each student sit in his/her regular seat and number off each student one through five. Next, call all students that were given the number one to sit at a table together, then the twos, threes, etc. The groups should be diverse in terms of gender, ethnicity, race, and ability.

Student and Group Roles

Divide the task into four segments. For example, in a project about the California Gold Rush, you may divide the lesson into the following topics: 1) Businesses that began as a result of the Gold Rush, 2) How they panned for gold, 3) Who were the gold seekers who moved to California, and 4) Where were the successful gold mines.

Assign each student in each group one of the four segments. Students who are assigned the same segment may meet to form an "expert group." The members of each expert group work together to learn the topic, making sure each member understands the information. During this time, the experts construct a plan to teach their topic to the members of their jigsaw cooperative group.

Final Outcome

Students then return to their jigsaw cooperative group. Each student teaches his or her topic to the members of the group. There is a sense of positive interdependence among the members of the groups. To demonstrate knowledge, each jigsaw group may present a summary of their understanding to the whole class.

Benefits of Heterogeneous Groups

Research shows that jigsaw cooperative groups, when students work together in heterogeneous groups, may improve race relations within a classroom (Eby, 1994). Working together within teams generates a more accepting and realistic view of other students than competitive and individualistic learning experiences.

Jigsaw cooperative groups provide an equitable learning environment. When students of different ethnic, racial, and linguistic backgrounds work together, they develop respect for one another. In jigsaw groups, students are interdependent. Social acceptance of others increase because students need to help each other and learn from each other. Also, research shows that cooperative learning improves the social acceptance of mainstreamed students with learning disabilities (Slavin, 1990).

Students' academic achievement is raised when all students work together towards a common goal. High achieving students learn tolerance and understanding of individual differences. Lower achieving students develop a greater understanding of subject matter. Students are highly motivated to work within a group. Also, teamwork helps students learn interpersonal skills, which is especially beneficial to second language learners.

[Return to Top]

Preamble

Australia’s future depends upon each citizen having the necessary knowledge, understanding, skills and values for a productive and rewarding life in an educated, just and open society. High quality schooling is central to achieving this vision.

This statement of national goals for schooling provides broad directions to guide schools and education authorities in securing these outcomes for students.

It acknowledges the capacity of all young people to learn, and the role of schooling in developing that capacity. It also acknowledges the role of parents as the first educators of their children and the central role of teachers in the learning process.

Schooling provides a foundation for young Australians’ intellectual, physical, social, moral, spiritual and aesthetic development. By providing a supportive and nurturing environment, schooling contributes to the development of students’ sense of self-worth, enthusiasm for learning and optimism for the future.

Governments set the public policies that foster the pursuit of excellence, enable a diverse range of educational choices and aspirations, safeguard the entitlement of all young people to high quality schooling, promote the economic use of public resources, and uphold the contribution of schooling to a socially cohesive and culturally rich society.

Common and agreed goals for schooling establish a foundation for action among State and Territory governments with their constitutional responsibility for schooling, the Australian Government, non-government school authorities and all those who seek the best possible educational outcomes for young Australians, to improve the quality of schooling nationally .

The achievement of these common and agreed national goals entails a commitment to collaboration for the purposes of:

further strengthening schools as learning communities where teachers, students and their families work in partnership with business, industry and the wider community

enhancing the status and quality of the teaching profession

continuing to develop curriculum and related systems of assessment, accreditation and credentialing that promote quality and are nationally recognised and valued

increasing public confidence in school education through explicit and defensible standards that guide improvement in students’ levels of educational achievement and through which the effectiveness, efficiency and equity of schooling can be measured and evaluated.

These national goals provide a basis for investment in schooling to enable all young people to engage effectively with an increasingly complex world. This world will be characterised by advances in information and communication technologies, population diversity arising from international mobility and migration, and complex environmental and social challenges.

The achievement of the national goals for schooling will assist young people to contribute to Australia’s social, cultural and economic development in local and global contexts. Their achievement will also assist young people to develop a disposition towards learning throughout their lives so that they can exercise their rights and responsibilities as citizens of Australia.

[Return to Top]

Goals

1. Schooling should develop fully the talents and capacities of all students. In particular, when students leave school, they should:

1.1 have the capacity for, and skills in, analysis and problem solving and the ability to communicate ideas and information, to plan and organise activities, and to collaborate with others.

1.2 have qualities of self-confidence, optimism, high self-esteem, and a commitment to personal excellence as a basis for their potential life roles as family, community and workforce members.

1.3 have the capacity to exercise judgement and responsibility in matters of morality, ethics and social justice, and the capacity to make sense of their world, to think about how things got to be the way they are, to make rational and informed decisions about their own lives, and to accept responsibility for their own actions.

1.4 be active and informed citizens with an understanding and appreciation of Australia’s system of government and civic life.

1.5 have employment related skills and an understanding of the work environment, career options and pathways as a foundation for, and positive attitudes towards, vocational education and training, further education, employment and life-long learning.

1.6 be confident, creative and productive users of new technologies, particularly information and communication technologies, and understand the impact of those technologies on society.

1.7 have an understanding of, and concern for, stewardship of the natural environment, and the knowledge and skills to contribute to ecologically sustainable development.

1.8 have the knowledge, skills and attitudes necessary to establish and maintain a healthy lifestyle, and for the creative and satisfying use of leisure time.2. In terms of curriculum, students should have:

2.1 attained high standards of knowledge, skills and understanding through a comprehensive and balanced curriculum in the compulsory years of schooling encompassing the agreed eight key learning areas:

the arts;

English;

health and physical education;

languages other than English;

mathematics;

science;

studies of society and environment; and

technology.

and the interrelationships between them.

2.2 attained the skills of numeracy and English literacy; such that, every student should be numerate, able to read, write, spell and communicate at an appropriate level.

2.3 participated in programs of vocational learning during the compulsory years and have had access to vocational education and training programs as part of their senior secondary studies.

2.4 participated in programs and activities which foster and develop enterprise skills, including those skills which will allow them maximum flexibility and adaptability in the future.

3. Schooling should be socially just, so that:

3.1 students’ outcomes from schooling are free from the effects of negative forms of discrimination based on sex, language, culture and ethnicity, religion or disability; and of differences arising from students’ socio-economic background or geographic location.

3.2 the learning outcomes of educationally disadvantaged students improve and, over time, match those of other students.

3.3 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students have equitable access to, and opportunities in, schooling so that their learning outcomes improve and, over time, match those of other students.

3.4 all students understand and acknowledge the value of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures to Australian society and possess the knowledge, skills and understanding to contribute to, and benefit from, reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.

3.5 all students understand and acknowledge the value of cultural and linguistic diversity, and possess the knowledge, skills and understanding to contribute to, and benefit from, such diversity in the Australian community and internationally.

3.6 all students have access to the high quality education necessary to enable the completion of school education to Year 12 or its vocational equivalent and that provides clear and recognised pathways to employment and further education and training.

More information about the work of MCEETYA in relation to the National Goals for Schooling, the measurement of student performance and the National Report on Schooling in Australia can be found on the MCEETYA website.

[Return to Top]

Email this page

Print this page

IN THIS SECTION

Policy, initiatives and reviews menu

National Goals for Schooling in the Twenty-first Century

School education policy, issues & reviews

Copyright | Disclaimer | Privacy | Feedback

Friday, November 10, 2006

Examination Semester 2 2006 ED4236/1120

According to Hattie (2003) there are five attributes of an expert teacher :

1. Expert teachers can identify essential representations of their subject.

- Deeper representations about teaching and learning

- Adopt a problem solving stance to their work

- Can anticipate, plan and improvise as required

- Are better decision makers

2. Expert teachers guide learning through classroom interactions

- Create optimal classroom climate for learning

- Have multidimentionally complex perception of classroom situations

- Are more context dependent and have high situation cognition

3. Expert teachers monitor learning and provide feed back

- Are adept at monitoring student problems, levels of understanding and progress and provide relevant, useful feedback

- Develop and test hypotheses about learning difficulties or instructional strategies

- Their cognitive skills become automatic

4. Expert teachers attend to affective attributes

- Have high respect for students

- Are passionate about teaching and learning

5. Expert teachers can influence student outcomes

- Engage students in learning and develop in their students self regulation, involvement in mastery learning, enhanced self efficacy and self esteem

- Provide appropriate challenging tasks and goals for students

- Have positive influences on students achievement

- Enhance surface and deep learning

A few of my own thoughts about the characteristics of an expert teacher

- Display and believe in a positive and loving outlook on the world

- Has a genuine passion for their subject area that flows far beyond the classroom and school schedule

- An awareness of the power of facilitating students not only to think and act but how to feel about all aspects pertaining to the subject matter and more

- Expert teachers are enlivened by interacting with students and others that inturn resonates like ripples in a pond out into the wider world.

- Can self regulate their emotions and provide a sustainable approach to the rigours of the profession

Oct. 1. 2006.

Just a little prayer for us struggling teachers on the road to becoming experts.

May I be brave enough to embrace a new world view as

Espoused by Margaret Wheatley.

May I develop the wisdom of recognising Gardners Nine Intelligences

In my students.

May I gain true insight in teaching Glasser’s six basic needs of Survival;

Power, Love, Belonging, Freedom and Fun.

May I have the strength and courage to incorporate Hatties guide for expert teachers

Into every class, every day.

May I develop awareness of the full scope of the Constructivist approach

To education.

And may I develop the selflessness to recognise that students need to be encouraged to be creative in their approach to their own education and

Empowered in making decisions in relation to their lives.

A SPEECH

ON THE QUEST TOWARDS BECOMING EXPERT TEACHERS

Fellow teachers,

We have embarked upon a noble quest

We need to be firm in our resolve to work together

To articulate our vision, to dare to love.

There is an urgency in the air

The world is crying out for a new way of seeing

For a new reality on which to base our hopes and dreams.

We have lost our way as a culture and we know this.

The old ways of doing things does not work anymore

We no longer want to be part of a world that preys on our fears

We do not want our children to inherit a world

In which they carry the burden of our lack of courage.

There is much work to be done.

Firstly on a personal level to open our hearts, to be brave, to be authentic

And secondly on a professional level to sow the seeds of higher order learning

in our students so that they can develop the necessary skills

To analyse, evaluate and create empowered lives for themselves

And enable them to flower into strong, confident and creative individuals who will facilitate change through living fulfilling lives.

We can achieve this through providing a safe, secure place

where they feel a sense of belonging and feel loved and valued

And to develop the personal sense of power and to recognise that freedom is the handmaiden of responsibility to refine the attributes of thinking, feeling and willpower with a sense of fun and adventure.

We need to support students to support each other in their endeavours

And to recognize and work with the different intelligences inherent in every one

And to view these as assets both inside and outside the classroom.

We need to offer positive and timely feedback regarding our students work

To provide the very best quality instruction whilst facilitating appropriate challenges

And promote effective classroom interaction.

The road is long and hard. There are no shortcuts

We want to connect with each other in ways that are meaningful

We want to commit to each other in ways that empower all

Not only on a national level

And not only on a personal level

But on a soul level.

So let us begin. Let us embark upon our quest

Let our creativity become our journey and our goal

And enthusiasm and passion the path by which we achieve this

And let love be the map of the heart that will guide us.

Above are some personal characteristics and motivation for embarking upon the quest of becomming a Expert teacher.

Above are some personal characteristics and motivation for embarking upon the quest of becomming a Expert teacher.Question 2: How do the theories of Jean Piaget and Lev Vygotsky complement each other to provide the underpinning for the Constructivist Theory of Education?

Essentially the theories of Piaget and Vygotski complement each other in as much as Piaget asserts that the individual is the agent of cognitive development and Vygotski asserts that society is the agent of cognitive development. The theories of both men underpin the Constructivist Theory of Education in the following ways.

"Every function in the child’s cultural development appears twice, first on a social level and later on an individual level, first between people / interpsychological, then inside the child / intrapsychological (aspects of Gardners 9 Intelligences Theory) This applies equally to voluntary attention, to logical memory and the formation of concepts. All higher functions originate as actual relationships between individuals (Wheatley’s Relationship Theory)" Vygotski (1978)

The second aspect of Vygotski’s theory is the idea that the potential for cognitive development depends on the Zone of Proximal Development, a level of development attained when children engage in social interaction. Full development of Z.P.D. depends on full social interaction. The range of skill that can be developed with adult guidance or peer collaboration exceeds what can be achieved alone (Constructivist education tenet)

(from http://tip.psychology.org/vygotsky.html) (italics added by me)

Piaget explained the implications of his theory in all aspects of cognition, intelligence and moral development. His principles where 1. Children will provide different explainations of reality at different stages of cognitive development. 2. Cognitive development is facilitated by providing activities or situations that engage learners and require adaptation. 3. Learning materials and activities should involve the appropriate level of motor or mental operations for a child at a given age . 4. Use teaching methods that actively involve students and present challenges.

These aspects of Piaget's theory suggest the further work of Brunner's Constructivist Theory where learners construct new ideas or concepts based on their current/past knowledge; where the learner selects and transforms information, constructs hypotheses and makes decisions relying on a cognitive structure to do so; and where the cognitive structure provides meaning and organization to experience and allows the individual to go beyond the information given.

(from http://tip.psychology.org/bruner.html)

Question 3: In the use of Board of Studies syllabuses, explain the use of the following documents at school level: Scope and Sequence, Teaching Programme, Assessment Program. Evaluate the part that each of these documents plays in determining what is taught?

Scope is time allocated to a topic.

Sequence is the order in which topics are taught.

Teaching Programme:

- Divided into topics or modules

- Identify syllabus requirements

- Students learn about and learn to

- Teaching/Learning strategies

- Resources

- Assessment

- Registration/evaluation

Assessment Program is the activities of a teacher to gain information about knowledge skills and attitudes of the students.

The role of the expert teacher is to take the sylabus as the 'clay' and mold it into excellent outcomes for students.

The expert teacher with relation to the syllabus does the following:

1: Deeper representations about teaching and learning

2: Problem solving

3: Anticipate plan and improvise as required by the situation

4: Identify what decisions are important and which are less important

5: Enhance surface and deep learning over and above syllabus requirements and recommendations.

(from Teachers_Make_a_Difference_Hattie.pdf)

BOS website -> Syllabus -> Local Resources and needs -> Scope and Sequence/Program/Assessment plan.

Evaluation:

The scope and sequence of the BOS syallabus offers broad directions in what is taught and in what order. When I teach photography I refer back to the syllabus as terms of reference for covering all relevant and appropriate areas for student learning. It provides effective guidance to new teachers such as myself and a framework for which to build my teaching programme.

The teaching programme that I developed from the syllabus was made easier by using a grid of learning outcomes. I constructed imaginative lesson plans by utilising the recommendations of the syllabus and these have promoted students to explore their capabilities, and evaluate, create and reflect on the tasks.

The assessment program offers information about the knowledge skills and attitudes attained by students. Built into this assessment criteria is the evaluation of the program which determines my effectiveness as a teacher and the program I am presenting in whole or part. This provides insight into areas that work and areas that need further modification in order to promote effective learning outcomes.

Thursday, October 12, 2006

This Divine Element LOVE

Wheatley I agree really resinated the spirit of a living changing community, and not to fear charge or disruption. I loved the understanding about greeting differences in others and the ideas of management, growth and re structure.

I see our school as this liquid ball spinning and growing and all of us, our colleagues keep the ball from dropping none of us able to stop it, or hold it and it continually spins, unfolds and grows.

I found this quote from Steiner "Theosophy" and for me, it really gives my calling to teaching meaning. Lifes so short I feel one must feel worth and value in a life and the greatest gift, being part of a loved community. Thank you, for your Love, Support and Fun .

Wednesday, October 11, 2006

innovativeforu

A SPEECH

ON THE QUEST TOWARDS BECOMING EXPERT TEACHERS

Fellow teachers,

We have embarked upon a noble quest

We need to be firm in our resolve to work together

To articulate our vision, to dare to love.

There is an urgency in the air

The world is crying out for a new way of seeing

For a new reality on which to base our hopes and dreams.

We have lost our way as a culture and we know this.

The old ways of doing things does not work anymore

We no longer want to be part of a world that preys on our fears

We do not want our children to inherit a world

In which they carry the burden of our lack of courage.

There is much work to be done.

Firstly on a personal level to open our hearts, to be brave, to be authentic

And secondly on a professional level to sow the seeds of higher order learning

in our students so that they can develop the necessary skills

To analyse, evaluate and create empowered lives for themselves

And enable them to flower into strong, confident and creative individuals who will facilitate change through living fulfilling lives.

We can achieve this through providing a safe, secure place

where they feel a sense of belonging and feel loved and valued

And to develop the personal sense of power and to recognise that freedom is the handmaiden of responsibility to refine the attributes of thinking, feeling and willpower with a sense of fun and adventure.

We need to support students to support each other in their endeavours

And to recognize and work with the different intelligences inherent in every one

And to view these as assets both inside and outside the classroom.

We need to offer positive and timely feedback regarding our students work

To provide the very best quality instruction whilst facilitating appropriate challenges

And promote effective classroom interaction.

The road is long and hard. There are no shortcuts

We want to connect with each other in ways that are meaningful

We want to commit to each other in ways that empower all

Not only on a national level

And not only on a personal level

But on a soul level.

So let us begin. Let us embark upon our quest

Let our creativity become our journey and our goal

And enthusiasm and passion the path by which we achieve this

And let love be the map of the heart that will guide us.

innovativeforu

Oct. 1. 2006.

Just a little prayer for us struggling teachers on the road to becoming experts.

May I be brave enough to embrace a new world view as

Espoused by Margaret Wheatley.

May I develop the wisdom of recognising Gardners Nine Intelligences

In my students.

May I gain true insight in teaching Glasser’s six basic needs of Survival;

Power, Love, Belonging, Freedom and Fun.

May I have the strength and courage to incorporate Hatties guide for expert teachers

Into every class, every day.

May I develop awareness of the full scope of the Constructivist approach

To education.

And may I develop the selflessness to recognise that students need to be encouraged to be creative in their approach to their own education and

Empowered in making decisions in relation to their lives.

innovativeforu

LOVE AND OTHER FOUR LETTER WORDS

Sept. 28. 2006.

Love, now there’s a word you don’t see in the syllabus. And why not? Too revolutionary? Too seditious? Too close to the heart? May be all these and more. Hattie (2003) implies it (love) in the dedication and commitment shown by expert teachers. Wheatley (1999) really takes the ball and runs with it and opens up a whole new level of challenge for teachers to open their hearts.

The little that I know of love inspires me in my personal and professional life. I see and feel such need for an open hearted approach to learning and teaching. Students are confronted with very real and complex issues earlier in their lives than I experienced at their age and often the are grasping for the rudimentary tools with which to deal with their dilemmas. My own strategy when connecting with students is to try and imbue the encounter with authenticity and say to myself a silent “Namaste”, the Hindu greeting that says “I see the god in you”. This is easier on some days than others and with some students more than others. On a more active level I endeavour to “sow seeds.” I have a fairly gregarious and earthy personality and enjoy connecting with students in a mature, humorous and positive way. It is part of Rudolf Steiners “ Thinking, Feeling, Willing”, philosophy that sets the daily rhythm of school life and provides conscious and unconscious cues to students and staff. I find that humour mixed with compassion and wisdom speak non verbally to the human heart. This is where I try to make inroads in my connections with myself and others. I hear myself sounding like some one that’s read too much Wheatley. Not a bad thing.

I am all too aware of the pitfalls of making connections through relationship if one is not fully committed or conscious. My experiences as a Youth Worker brought home the seriousness of making mistakes and the far reaching consequences of reacting out of ignorance. Hattie (2003) hits the nail on the head when he states that the expert teacher “makes the lesson uniquely their own, by changing, combining and adding to them according to the students needs and their own goals.” And where, according to Blooms Taxonomy, deeper learning is facilitated by the teacher to enable the higher order thinking in a student that they not only Remember, Understand and Apply what is learned in the classroom but then go on to develop the skills to Analyse, Evaluate and Create from this information.

Monday, September 25, 2006

A PATH WITH HEART

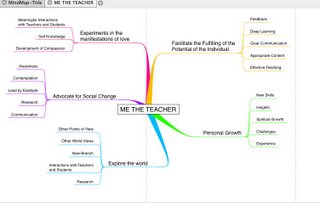

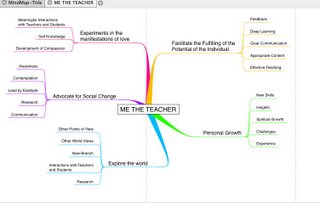

In the Saturday class with Tony McArthur he asked us to take five minutes and create a mind map exploring the reasons why we teach. It was a good opportunity to spontaneously “free associate” with myself about my reasons for teaching and to consider what my “spin” is, that is, to identify what is important to me and what I want to pass on.

So what does all this mean? I like the term “making connections in terms of relationships”. The word “connection” (Latin: necto; to bind), is one of the buzz words in the Byron Shire and it’s a good one. People here don’t “ring”each other or “meet up”, they connect. Regardless of this New Age speak, it’s rings true of individuals and communities trying to consciously interact with each other. This, I think is a response to the myriad of pressures upon us all in “post-modern life” and how these stresses can creep up on us and sometime overwhelm us and all of a sudden we ( I ) find that I’ve created emotional walls that start to separate me from other people. I get too self absorbed to connect. I am trying to build into my daily meditation a simple chant that stays in my heart all day. It goes like this,” Don’t forget to smell the roses” Nothing deep or profound, not even original, just an intermittent reality check.

I’ve been reading a paper by Margaret J Wheatley (1999) and she is a strong advocate of connections and networks. I find her writings refreshing, stimulating and in some instances, revolutionary. Here is someone speaking from the heart. Whilst I enjoy her approach and honesty there are a few issues that she raises that I feel I need to reply to in relation to me and my outlook as a teacher and individual trying to “make connections in terms of relationships”.

In Wheatley’s paper, “Bringing Schools Back to Life: Schools as Living Systems” (1999) she uses certain words/concepts that elevate her ideas to a universal level that bypasses the head (rational/intellect) and goes straight to the heart (irrational/feeling) She uses words and phrases such as “learning to partner with confusion and chaos as opportunities for real change…. participating in the mystery (of life)…. Surrender….to factor in instability, chaos, change and surprise”.

Wheatley quotes and gives anecdotal examples from Masters such as Morihei Ueshiba, the founder of the martial art of Aikido. The idea of using the wisdom of accomplished “Masters” in their field is nothing new to the West, especially in education and the arts but where Wheatley offers a” revolutionary edge “ is to include the wisdom of Eastern mystical masters and applying their insights into the Western education system.

I feel that whilst Wheatley offers a viable challenge on a profound and fundamental level to teachers and individuals to begin a journey that embraces change, her article doesn’t offer (nor does she acknowledge) what strategies to adopt when things go wrong and how to deal with this on a personal level. She insists that we all need to let go of the reigns of control and trust in the “dance of life”. I understand this and have experimented and experienced this “letting go” and have tasted the fruits of surrender. It’s a big call to expect individuals to heed the call” and take a leap of faith into he unknown” either personally or professionally.

I read a book recently by a Buddhist nun Pema Chodron (Shambala Publications 2000) called ‘When Things Fall Apart: Heart Advice For Difficult Times”. This book concentrates on the Buddhist perspective of bringing order into disordered lives. This book offers insights and practical advice on how to use what you have handy in these difficult situations namely, your despair, painful emotions and negativity as tools to begin to begin to cultivate wisdom, courage and compassion.

It is signposts like this along the way that I draw a true sense of direction. They offer fundamental building blocks for psychological health and as a guide for navigating through what Wheatley calls the “instability, chaos, change and surprise” in our lives. I have found that the Buddhist perspective of life and death doesn’t shy away from looking for and confronting and integrating the dark side of the individual and collective experience and offers easy to follow guidelines for cultivating personal consciousness and awareness of our whole selves. As the eminent Swiss psychologist Carl C Yung states that the “shadow is ninety nine percent pure gold”. Here Yung is emphasising that the seeds of true personal growth are nurtured in our fears and insecurities and by facing these fears the seed germinates and grows to it’s full potential when we develop our courage to love and turn the darkness into light.

Some quotable quotes (and potential mantras)

A new world is just a new state of mind. John Lennon.

Be the change you want to see in the world. Mohandas P. Gandhi

And a prayer to finish on

Lord grant me the courage to change the things I can,

The humility to accept the things I can’t and

The wisdom to know the difference.

Amen.

References;

Wheatley,M.J. Bringing Schools Back To Life: Schools as Living Systems

In Creating Successful School Systems: Voices from the university, the field and the community. Christopher-Gordon Publishers, September 1999.

Yung, C.J. Memories, Dreams, Reflections. Harper Collins London 1983

REFLECTIONS ON MY EFFECTIVENESS AS A TEACHER

So what are the fruits of my idealism/realism combo? And why do I find teaching an effective vehicle for these realistic ideals? I recognise that the quest to become an expert teacher does not happen in a vacuum. The personal challenges and tasks facing the individual need to be confronted, the experiences learnt from and used for growth. It’s as if the teacher has to become a student of life and assume the mantle of an alchemist of old, and learn the art of turning the lead of everyday experience in the classroom into the gold of the wisdom of an expert teacher. In other words, Know thy self.

As my wife so sagely offers, that’s all well and good, but how do you truly feel?

Ok, one reason for the lateness of this journal entry is that my HSC Design and Technology students have just reached critical mass with the finishing of their major works. This has been a work in progress since October 2005. The students, like myself, have experienced the whole gamut of human experience from the heights of inspired confidence to complete disillusionment. With regard to my effectiveness as their teacher, I have spoken to mentor teachers, read about other teacher’s experiences, talked to peer teachers and done much soul searching and still I wrestle with uncertainty.

The writings of Margaret Wheatley(1999) have cast light on my dilemma and illuminate my way somewhat with their perspectives on uncertainty, the constant of change and the ever present challenge to embrace my fears. In my daily ruminations and reflections I try and apply them to the reality of my experience in the classroom and workshop. Needless to say some days are more “enlightened” than others. I endeavour to build effective working relationships with students and this tends to work well in a workshop with its informal and creative setting. Even within this context it is a constant juggling act, as it is in any relationship, where awareness, care, sensitivity and feedback (Hattie 2003) continually challenge me personally especially when that occupational hazard of fatigue sets in.

So far,so good. Recently, as stated earlier, the reality of dealing with fatigue, and 8pm finishes each night with yr.12 students and their major works for two weeks prior to their completion deadline and trying to provide an effective classroom climate for eighteen year olds who are often tired, disinterested, over it and despondent due to personal problems can prove overwhelming at times. I realise that this is probably a common lament of teachers throughout the ages.

One strategy that I have adopted is endeavouring to capture the enthusiasm (from the Greek, entheos- inspired by god) of my students and encouraging them to base an idea for designing their major work on a product that they are passionate about. This generally provides impetus to varying degrees throughout the year for the students to self regulate and self motivate the completion of their usually significantly difficult design tasks. (appropriate challenging tasks and goals for students.(Hattie 2003) . This combined with regular feedback and encouragement with individual interviews regarding the state of their major works help build this working relationship.

One personal issue that I have found coming home to roost this year was the profound disappointment I found myself experiencing when students appeared to not really care about the subject and completion of the assessment tasks due to 1. Lack of commitment. 2.Poor time management skills and 3. Lazyness. I recognize several roles that I play in these situations. Firstly is my attachment to their perceived lack of interest and repeatedly fall into the trap of taking it personally. I find I have to consciously take stock of my own passion for the subject and realise that most students at some time are not going to share my enthusiasm and that they have many other subjects and are not always going to be inspired by me or the subject matter. The three issues I outlined above can easily be understood when I reflect that the students are only seventeen or eighteen years old and respond accordingly.

These times lead me to re evaluate my approach to becoming an expert teacher. I do tend to become intense about the importance of the subjects I teach and the need for the students to achieve the best that they and I can. This approach works well usually but sometimes my single mindedness can lead to my losing objectivity and becoming despondent at the thought of the students lack of interest. Of course the students do care and after talking to the students, other teachers and usually a good sleep, objectivity returns and I adjust my approach and “pace myself” and my passion and develop a better understanding of myself and my students. I recognize that I need to become more professionally objective and be more conscious of my personal and professional boundaries and develop a “wider scope of anticipation and more selective information gathering (Cellier et al., 1997) Because of their responsiveness to students, experts can detect when students lose interest and are not understanding. (Hattie 2003)

References: Hattie,J. Building Teacher Quality. Australian Council for Educational Research Annual Conference. University of Auckland. 2003.

16 Sept 2006

The BOS Itinerant Markers visited the school today to assess the Major Works and Design Folios of my HSC Design and Technology students and whilst they are tight lipped about their thoughts and marks they did inform me that three of my students Major Works have been short listed to be considered as exhibits at the Powerhouse Museum in Sydney for Design Week later this year because of the students commitment to excellence in the complexity of their design, innovation and originality. YEE HAA!

Sunday, September 24, 2006

Reflective Journal

REFLECTIVE JOURNAL

I came to teaching, (or did it come to me?) in a rather circuitous fashion. I had never entertained the idea of becoming a teacher until I was in my forties and even then my primary motivation was to secure a job that offered a regular pay cheque. Prior to teaching I had many jobs as a Builder, drainage contractor, youth worker, project manager, furniture designer/maker, traveller etc. Surprisingly enough, I find myself reflecting on my current role as a teacher and the previous smorgasbord of jobs and see a pattern emerging, indicating that these past “jobs” and experiences have prepared me for and lead me to my current “vocation”.

Experience in the building industry provided me with insights into the process and nature of structures. I developed strength and willpower in the process of hand digging long trenches through rocky ground. Youth work taught me patience and understanding. Fine furniture making demanded discipline and precision. The wonderment and awe experienced in immersing myself in diverse cultures have all contributed to providing essential growth, insight and skills for teaching. This current study through Notre Dame University is the current stage of my journey in exploring, gathering, refining and sharing of these ideas and insights.

I have been teaching at Shearwater for six years now and enjoy the challenges that teaching/learning involves. These constant challenges (daily) that arise provide grist for the mill for my personal and professional growth. Prior to this current study with Notre Dame University I had not engaged in any formal study apart from a two year stint of a Social Work degree. I consciously discontinued this study at twenty one years of age, full of ideals and optimism and a realization that whilst my fellow students and I were being groomed to be “good” social workers we were also becoming facilitators of the very social system that reinforced the polarization of a power hierarchy that kept the our disenfranchised “clients” in a downward spiral of poverty and disempowerment. So in the end I came to realise that if you weren’t a revolutionary (social worker) at heart then you weren’t going to be worth anything to the people that you are trying to “help”.

Twenty five years on and a little wiser, life, in it’s infinite wisdom has watered down that youthful idealism with a healthy amount of realism and I find myself by accident (or design?) teaching in an educational environment that encourages and supports revolutionary thinking and teaching based on the theories of Rudolf Steiner. A thinking that nurtures the fundamental growth of the individual and supports and empowers them through their own creative impulse. I now find myself exploring my own creative passions of Industrial Design and Photography and the sharing of these skills and insights in turn empowers me both as a teacher and individual.